Anyone who suggests that mining photography is easy doesn’t know what they are talking about. The light is nearly always hokey so one must compensate for this by working longer hours. So often I find myself working late into the night so that I can take control of one of the most important elements of photography. Because the word "photography" means to paint with light…

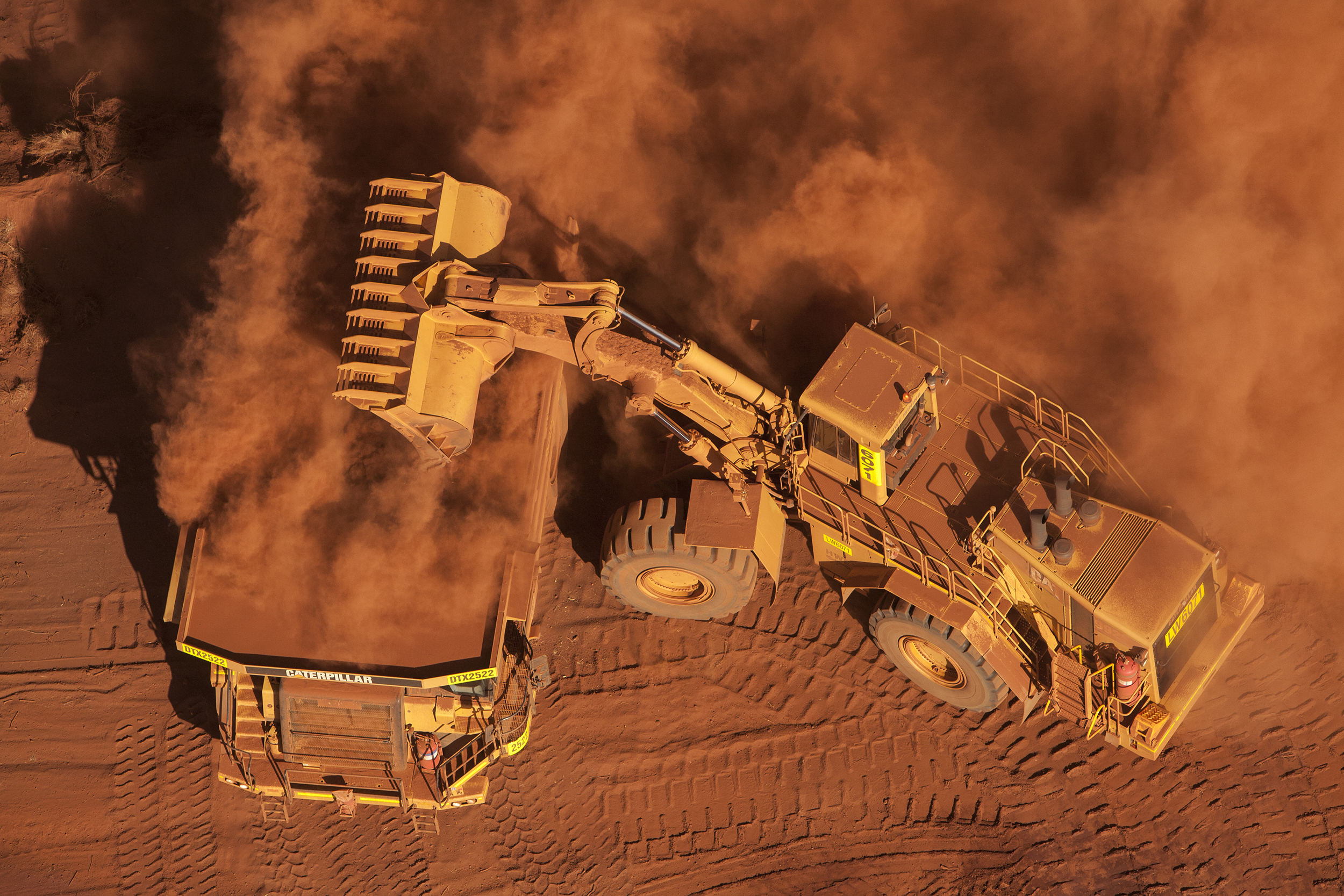

What is also difficult about mining photography is the fact that pretty much most pits around the world look the same. The gear is the same. The pits look the same, save for some variations in depth and colour. And many of the people look the same because they are all wearing the same clothing. And more often than not they are wearing bright yellow or orange clothing which is awful for photography.

I try to compensate for all of this by looking for features that are unique to each of the places in which I work. It might be the commodity itself (for example, sulphur is bright yellow), or it might be the location (a huge boab tree on the edge of a pit in western Mali for example). Or it might be behaviours that are different to what the rest of us are used to (for example, a hundred or more mine workers in prayer in their fluorescent uniforms in a remote part of Senegal).

History is a huge part of my approach to mining photography. So I’m always searching for those images that, in the years to come, will tell a story about a place in time. And that’s why I have taken aerial photos of the Port Hedland port every year since 2005. It’s why I’m in the advanced stages of a major book project to document the world’s primitive miners: people around the world mining as they did in the Goldfields back in the nineteenth century. It is also why I produced a large-format coffee table book on Rio Tinto’s rail business that in 2016 celebrated its 50th year of operation in the Pilbara.

Mining photography is hard work. But done right it can be immensely rewarding and spectacular. You just have to be prepared to put in the yards to do it properly.

I have been involved with the mining industry in some capacity for much of my working life. Initially, in my business life. And then, for the last 15 years or so it has been as a photographer working on some of the world’s largest mining projects.

The change in the global mining industry these past 15 years has been truly staggering. My mining photography work began at the cusp of the China mining boom. Just as companies such as Fortescue Metals and Atlas iron were born. And just as major new mines and ports and railways were being built to go with all of that. Pilbara iron ore production over the past 15 years has increased from around 220 million tonnes per annum to the current incredible 700 – 800 or so million tonnes.

In late 2008 I was perhaps one of the very few photographers to document the impact of the global financial meltdown. Whole mines were mothballed and ports came almost to a standstill. I remember at Dampier the port sitting at near empty with ships being refused entry until they could produce letters of credit. In Port Hedland ships sat on berth while ship loaders sat at a standstill. It was an amazing time, seen by me, right around the region, from a helicopter over a ten day period.

Internationally, my mining work has seen me travel around the world. To South America (Bolivia). To Central (India and Pakistan) North (China) and South-East Asia (Indonesia, Papua New Guinea). And to Africa (Ghana, Mali, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, South Africa, Malawi, Cote D’Ivoire, Guinea).

In China I’ve worked inside some of that country’s largest steel mills. I’ve also photographed some of its port infrastructure, including what was then the world’s largest iron ore import terminal in Qingdao. In Pakistan I’ve worked at very high altitude among some of the world’s highest mountains. While in Bolivia I’ve worked on perhaps the world’s most dangerous mountain: one that has claimed the lives of four to eight million people since 1545.

My mining work has seen me working at all elements of the value chain (exploration, development, mining, rail, ports and processing) across a variety of commodities (coal, copper, gold, iron ore, nickel, silver, stone, sulphur, uranium, zinc, etc.).

Steel Mill Landscape, China, 2014. Edition of 3.